Kindergarten, 1974/75 (5YO)

One day when walking to kindergarten, I had dawdled along the way, and I was late to school. We were supposed to arrive during lunch recess, and play in the kindergarten playground until the bell rang for everyone to come in.

This time, when I got there, the bell had already rung and the playground was deserted. So I knew I was late. I didn’t know what happened to people who were late but I was pretty sure it wasn’t anything good. I was terrified of having to walk in there in front of everyone, so I turned around, walked back home, sneaked into the house via the side door, and hid in the basement. My “plan” was to hide down there until it was time to come home, at which point I’d come out and pretend that I’d been at kindergarten all day.

Mom found me down in the basement at some point – I have a hazy idea that I had come out of the “fruit room” to see what time it was, and had not closed the door fully, which she noticed. (Knowing how paranoid she was about checking that all the basement windows were locked every single night, I expect there was a lot more fuss when she suspected an intruder in the house, but I don’t remember much about being found out.)

She took me back to school, or possibly walked me there the next day, and they tried to tell me that the bell didn’t always ring at the same time — so that if it ever happened again I’d go inside the school, I guess.

I’ve already written about the day I “ran away from home”, when I was around 4YO.

I “ran away” by going up the sidewalk until I couldn’t see my house any more. Once I was out of sight of our house, I plonked myself down in front of the second house from ours, maybe 300 feet up the hill.

I don’t know how long I sat out there, but I eventually got tired of being a runaway and went home. I found out much later that the neighbor had seen me sitting on the sidewalk in front of their house and called my mom, WHO JUST LET ME STAY OUT THERE. Where I wasn’t a bother to her.

Her excuse was that well, once the neighbor called, then she knew where I was, so that was OK.

Neither of these stories were ever told as cute little kid stories. You know, the kind that get told when you bring a date home to meet the family.

I suspect this is because there is something really off about them: the lack of concern shown by my mother for her younger daughter is disturbing.

It might not be as obvious in the school story — it’s easy to miss (or deliberately ignore) if you don’t know that my elementary school was 3/4 of a mile away from our house and my mother sent me, a 5YO little girl, to walk there every day by myself.

Easy prey for anyone who just might have noticed a little redheaded girl walking alone, at the same time, day after day.

(And let me tell you, after a lifetime of living it, people notice redheads in situations when everyone else is just part of the crowd.)

Her not being inconvenienced was more important than the fact that something horrible might happen to me.

It’s even more appalling when you add in that there was a known or suspected child predator in the area. This man lived alone, a few doors down from one of my best friends in elementary school. Every kid who walked home after school in that direction knew that if you climbed the steps and rang his doorbell, he would give you a few pieces of candy. Decades later, my friend told me that her mom had once cautioned her, “If he ever asks you to take the candy out of his pocket, don’t do it.”

[In contrast, with my sister there was once an elaborate chain of walking, a bus ride, and someone’s mother driving, in order that she attend a Catholic school. Maybe that’s the “excuse” that was made for my mother’s lack of care — that if it wasn’t a Catholic school, she wasn’t concerned about me getting there. Of course, that makes her a fine Catholic — but still a neglectful mother.]

Then there was the time one winter I was signed up for after-school ice skating lessons. This was not long post-divorce, possibly the very first year post-divorce, so I was about 8 or 9YO at most.

The lessons were Mom’s idea. It wasn’t time for us to spend together — she didn’t participate in or even come to the lessons to watch me skate — but the agreement was that she was supposed to come down to the Auditorium after work, and make sure I got home.

One night she forgot me. The lesson was long over, everyone else was gone, and my mother hadn’t come to get me. It was dark, and I was scared, and I didn’t know what to do.

I waited and waited in the lobby, alone and worried, hoping that Dad would come and get me. There was a pay phone in the lobby, but I didn’t have any money to use it.

Finally, an older gentleman came into the building, and although I was scared to do it, I also knew I had to — I asked him for a dime so I could make a phone call. He took me up to the office area, and they called the house. I don’t remember much else, but Dad was furious.

And then there was the continual problem of me walking the 4 blocks home from her apartment — by myself, in the dark.

This cropped up over and over again through the years. Mom didn’t see why she should walk me home, because then SHE would have to walk back in the dark by HER self.

I clearly remember her and Dad arguing about it once, at the front door, after Mom and I had walked home from church one Sunday. There was a clause in the divorce decree that said that visitation with Mom had to be “reasonable times and reasonable places” — a phrase that resonated throughout my childhood — and that she had to be responsible for our safe transportation to and from.

I can remember Dad clearly making the point that if I was sent to walk home from her apartment by myself, “something” could happen to me.

My mother’s literal, actual, word-for-word response to this was,

“But what if something happens to ME?”

So. Clearly she was keenly aware of the potential danger — when it pertained to her. And just as clearly, she was absolutely unconcerned about exactly those same dangers threatening her daughter.

While she was entirely aware of the hazards of a woman walking alone in the dark, she was perfectly fine with me doing it — apparently the idea that something might happen to me didn’t bother her at all, as long as it didn’t happen to her.

In the beginning, she would walk me to the front of the house and then wait for me to go in. She was supposed to stay until I turned off the light that was left on in the foyer, which would mean that I was safely inside.

At some point, my mother came up with the compromise that she would stand on the uphill corner, safe under the streetlight, and watch me walk the long downhill block to our house, past the wide open, empty park. This required a new “signal”, which was that I was supposed to flash the porch light on and off a couple of times once I got inside.

God only knows what the plan was if someone nefarious jumped out of the bushes and grabbed me as I walked the rest of the way alone to the house. (Well, of course there was no fucking plan, other than to keep herself safe at the top of the hill.)

I know that at some point Dad found out about the “compromise”, and he was mad about that too, but I don’t remember what might have been done about it.

My older siblings — who were of course not living at home during this period — while defending my mother’s loss of custody in The Divorce, once claimed that she couldn’t possibly have been neglectful, saying that she’d have had to be “leaving us in a car to go drink in a bar”, in order to REALLY be neglectful.

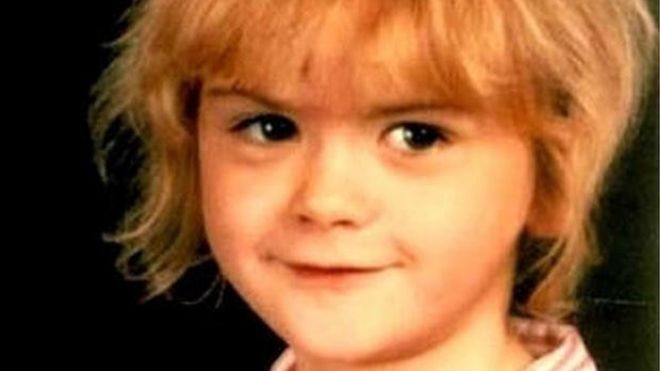

Now read this, and look at this little girl’s picture.

April Tinsley: DNA snares man in Indiana girl’s 1988 murder

DNA evidence links an Indiana man to the murder 30 years ago of an eight-year-old girl, police say.

John D Miller, 59, has appeared in court facing charges for the 1988 abduction, rape and murder of April Tinsley in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Police matched his DNA from used condoms to evidence found on the girl’s underwear, an affidavit says.

It also states he has confessed. The killer apparently taunted police and threatened other little girls.

The murder

On 1 April 1988, April was abducted while walking to a friend’s home.

Three days later, her body was found in a ditch 20 miles (32km) from her neighbourhood. She had been assaulted and strangled.

Despite finding DNA evidence on April’s underwear during the initial investigation, police failed to narrow down a suspect.

This story literally nauseates me. It makes my stomach heave.

This could have been me. And my mother would not have given a shit.

In fact, it’s taken me over a week to write this post, since I first read the news story — because it makes me so sick and appalled. Because what I realized — with the force of a punch to the gut — was that for my mother, me getting abducted would basically have been a huge positive for her.

- She would have gotten a ton of sympathy, and she always loved being a martyr and having people feel sorry for her.

- Me being gone would have eliminated a whole lot of work for her — especially since I was the youngest, which meant that I was the only thing keeping her from being able to do as she pleased all day.

- Finally, it would have been a “get out of jail free” card for absolutely anything the whole rest of her life.

Given all that, and all the times this issue cropped up over and over again in my childhood — when I read this news story the other day, it suddenly became very clear to me that my mother would have loved for me to disappear. It would have been great for her, just as it would have been great for her if Dad had died:

I have wondered just what would have made my mother happy at this point in the narrative. She needed and wanted Dad’s income, and refused to give up being provided for in the manner to which she had become accustomed — but she hated Dad, and living in the same house with him, as his wife, made her miserable, and by extension, everyone else too.

The only thing I can think of that would have “fixed” the situation would have been if Dad had conveniently died, and left her with all “her” kids and a big beautiful house, and a big insurance policy, so she would never have to work.

The really sickening part of it is that Mom had to be completely aware of what would have been likely to happen to me if I had been abducted on my way to school, or after the ice skating, or any one of hundreds of times I walked home alone. She was able to sexualize my father’s love for me and my brother’s pre-teen erection – she got both of those out of thin air, on her own. So the idea of someone sexualizing a little girl was not something she couldn’t comprehend. And again, she was obviously aware of the dangers of a woman walking alone.

Yet she let it happen, again and again, over years and years. And I heard from her own mouth how her safety was more important than mine.

Look back at April’s picture. Read what happened to her. And see if you can still claim that my mother was not neglectful.